MAMARONECK, NEW YORK – Carlo Gambino approached 12-year old Walter Shaw, Jr. after his father had been grilled that day by Senator John McClellan about his role in the mob’s multiple gambling rackets. “You remember one thing about these politicians, these judges, these big corporations”, the top boss of New York’s five crime families told the impressionable boy. “They have a license to steal,” he continued, “but we don’t need one. You remember that. Your dad’s not the bad guy, kid. They are the bad guys”.

Walter Shaw Sr. had been furnishing Gambino’s criminal enterprise with an ingenious little device of his own invention, that allowed the mob’s bookmakers to run a national gambling ring over the telephone undetected. Known as a “black box”, the FBI had confiscated a little over a dozen of them earlier that spring during a raid of the $3.5 million-dollar operation’s headquarters in New York’s Westchester County.

During his testimony, the former Bell Laboratories engineer admitted to inventing the modified version of a common phone tapping device known as a “cheese box”. Used by law enforcement to eavesdrop on phone conversations, the relatively simple device only worked if both telephones were wired. Shaw’s innovation allowed the same functionality on a single telephone, bypassing Ma Bell’s call tracking capabilities altogether and allowing bookies to make free, untraceable calls to the racket’s headquarters in Mamaroneck, NY.

Starting out in Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co.’s construction department in Miami, Florida in 1936, Walter Shaw briefly left the company and returned to climb up the phone company’s engineering ranks in 1941. Over the course of the following nine years, he would come up with several innovations, such as call-forwarding and the speakerphone to name just a few. After consulting with “other inventors”, Shaw decided that rather than relinquish his work to the telephone monopoly, he would quit his job start his own company.

Sometime around 1958, the Shaw-Tel Corporation was formed in New Jersey for the purpose of mass producing his speakerphone system, but shortly thereafter investors sued him for misappropriation of funds and obtained a $24,000 settlement against him in civil court. It was reportedly around this time that Shaw began developing his modified cheesebox and courting alternative sources of funding in the underworld.

Early on in that process, Shaw’s business partner in Miami, Ralph Satterfield, approached a private detective to pitch him on the idea. The detective, in turn alerted Southern Bell, which began tapping their phone lines almost immediately. Oblivious to the surveillance, Shaw struck a deal with Gambino family accountant, Archie John Gianunzio, to produce 200 black boxes and retail them for $1,000 a piece to bookies all over the country. By then, the Westchester County district attorney’s office, the New York State Police and the FBI were all hot on their trail as well, and in February, 1961, federal agents stormed Gianunzio’s houses in Mamaroneck confiscating 15 of the devices and taking the gangster into custody.

Shaw, who had been manufacturing the devices himself with Satterfield’s help at a warehouse provided by the mob, had left for South Florida just before the raids. Authorities only caught up with him in Miami, when he tried to hawk one of the devices for $1,500 in the presence of a detective for the State Attorney’s office. Arrested for a second time, Shaw attempted to jump bail and was again apprehended in New Jersey, where he was held at the Bergen County Jail, with bail set at $75,000 to await an extradition hearing.

In November, Shaw and his co-conspirators pled guilty to unlawful interference with the telephone company, which at the time was a civil charge that carried no criminal penalties. The McClellan Committee’s report was published the following year and recommended revising the Federal Communications Act of 1934 to include “criminal penalties for the unauthorized attachment of foreign devices to telephone equipment or facilities”. Shaw, for his part, would continue to improve on the design of his black box, which would morph into the much smaller “blue box” Steve Jobs would later claim was only the reason Apple Computers came to exist.

Southern Bell’s chief investigator, John D. Montgomery, testified in 1961 that the telephone company had already “devised several definite methods” for detecting the use of Shaw’s contraption in different parts of the country and expected that these methods would become more sophisticated in short order. Indeed, Shaw’s activities were easily tracked once they were identified, but the laws precluded any meaningful prosecution of the violations. In the meantime, a cottage industry of clandestine phone hacking devices sprouted from Seattle to Long Island, and a young generation of so-called “phone phreaks” grew right along with it.

By the time Walter Shaw, Jr. decided to join the Lucchese crime family at 16 to embark on his journey to become “the greatest jewel thief who ever lived”, according to a Florida police detective, hacking the phone company’s switchboards and land lines was turning into a national pastime for a certain segment of America’s youth: Blind kids.

Running Blind Through the Valley of Darkness

Joe Engressia was born blind to a school-picture photographer in Miami, Florida, and by the age of eight discovered that he could whistle his way into a making telephone calls. “The Whistler”, as he would come to be known by his admirers, didn’t understand the technical details of the seemingly magical skill until much later in life, but once his parents began encouraging his obsession with telephony, the young man with perfect pitch developed an uncanny ability to manipulate the acoustically-triggered radio frequencies traveling through the phone company’s cables.

Technical specifications for Southern Bell’s entire telecommunications system had been freely accessible to anyone who bothered to look in a public library since at least 1960. Volume 39, Issue No. 6 of the Bell System Technical Journalcarried an article titled “Signaling Systems for Control of Telephone Switching”, which listed Ma Bell’s pulses, frequencies and operator codes. All someone like Engressia or Shaw, for that matter, had to do was find ways to replicate them in order to breach the telephone monopoly’s infrastructure and bypass the master accounting computer that tallied all the billable charges.

One of the ways this was achieved revolved around the toll-free 800 numbers that Ma Bell introduced in 1967 as a way to reduce dependence on operators. By the following year, Engressia was enrolled as an electrical engineering student at the University of South Florida (USF) and still very much captivated by his mischievous hobby, which had other practitioners among a small, but growing, community of “phone phreaks”.

According to The Oracle, USF’s school newspaper, Engressia had one of his ‘readers’ – fellow students who would read aloud to him – transmit the contents of a technical telephone manual sometime in the fall of 1968, and made a one dollar bet with his cohorts that he “could beat the system” by whistling “like a bird” and placing free calls anywhere in the world.

Over the next few weeks, Engressia’s popularity soared as students lined up to test the visually handicapped magician. His ability became so sought after by curious classmates that he would enlist the help of “managers and promoters”. At approximately 1 a.m. on Halloween morning, Engressia made a mistake that revealed the breach to the phone company, which would track his activity from that point until he stopped placing calls two days later. Called into the Dean’s office a week later, Engressia’s world would take a drastic turn as he was suspended for the rest of the quarter and come under the surveillance of the FBI.

Gene Mason, head of security for the General Telephone Company of Florida, interviewed Engressia in the Dean’s office, and determined that the blind kid from Miami had no criminal intent, further suggesting that Engressia’s intellectual prowess might instead be of use to the phone company. The suspension would nevertheless move forward despite Engressia’s pleas to, at least, postpone it for the next school period.

Mason, who had long been monitoring phone conversations between underworld figures in Tampa on behalf of the FBI, like Santos Trafficante and Carlos Marcello, immediately turned over all evidence in the USF Whistler’s case to the federal law enforcement agency. Shortly afterwards, his story appeared in a local paper and Engressia began getting phone calls from other phone phreaks, including a full-fledged underground community of blind teenagers, who were commandeering General Telephone’s infrastructure in Southern California.

Exactly how these seemingly disparate phone phreak groups came to be is a matter of some controversy, but they undoubtedly served as the main recruiting ground for an imminent hacker movement still gestating. Engressia remained at USF until 1971, but did not graduate. He would move to Memphis, Tennessee, that year to pursue a trade with the phone company, but was repeatedly harassed by the FBI and prohibited from owning a phone.

Engressia’s very public ‘telephonic’ martyrdom was a major contributing factor in galvanizing the phone phreaks and establishing their nation-wide dissident networks, which began organizing conferences remotely on the phone company’s dime, precursors to the cyber hacker conferences that would characterize the latter movement’s origins in the early 1980s. But, while the Whistler may have been something of a phone phreak prodigy, he was in no way the only nor the first to uncover the very badly-kept secrets of the “largest machine in the world” and reveal them to the masses.

Tricks Are for Kids (Who Eat Cap’n Crunch)

The key to the phone phreaking universe revolved around the 2600 cycles-per-second (hertz) signaling frequency used by Ma Bell’s system. All of the phone company’s tones worked within a frequency range of 1600 to 2600 cps, but the latter was specifically tied to its free 800 numbers and opened the door to free long-distance calls for anyone who could transmit a 2600 Hz tone into the trunk lines followed by the tone patterns of the phone number they wished to reach.

There were different ways of achieving this, including Engressia’s straight up whistling technique to the prerecorded tones on cassette tapes used by many of the blind phone phreak networks, and the more sophisticated “blue box” devices, which used computerized circuits to produce the desired tones at the press of a button. Four years after a group of students at Harvard and MIT built a device that could reproduce Ma Bell’s 12 tone frequencies used to control telephone equipment in 1962, the Quaker Oates company started putting a small, plastic whistle in the boxes of a relatively new product called Cap’n Crunch that just happened to produce a perfect 2600 Hz tone.

First appearing on supermarket shelves in 1963, the sugary cereal featured a cartoon Naval captain on its colorful packaging – the anchor of an unprecedented marketing push by the ad agency Quaker had retained to execute a massive product launch using 80% of its entire marketing budget (five million dollars). The whistle, itself, would not be found inside the cereal boxes until 1966, but it nonetheless remained within the scope of the original branding project devised three years before by Compton Advertising, a Madison Avenue firm best-known for its six-decade relationship with major defense contractor and soap maker, Procter & Gamble (P&G).

Cap’n Crunch may have been the first cereal brand character with a backstory so intricate, it could rival Spiderman and some of the other popular Marvel superheroes that made their debut a year before. Compton hired the Jay Ward animation studio, which then had Rocky and Bullwinkle’s co-creator on its payroll, to write the history of the milk-bowl sailor. Born Horatio Magellan Crunch, the cardboard skipper had a Viking father named Sven, who was marooned in New England where he married a Native American girl, Gidget Running Star. Sent to England because of the limited curriculum of American schools, Crunch was kidnapped by pirates on the way there and taught to sail the seven seas.

Based on C. S. Forester’s fictional Captain Horatio Hornblower, Cap’n Crunch and his loyal hand-drawn crew would turn out to be an instant success among the 5 to 12 demographic thanks to the three 16-page comic books that accompanied the first boxes to hit the market, and a series of animated commercials telling Horatio Crunch’s story voiced by former officer from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and prolific voice actor, Charles Dawson “Daws” Butler, who also did the voice of Yogi Bear and Huckleberry Hound on Television.

A consistent output of merchandise and free “premiums” placed inside the cereal boxes kept the multi-million dollar marketing campaign sailing smoothly for several years. Crewmembers Alfie, Brunhilde, Carlyle and Dave, based on the first four letters of the alphabet, as well as the Captain’s faithful companion and owner of the infamous Bo’sun whistle, Seadog, gave the campaign numerous hooks to draw from for new toys and knickknacks.

In 1966, the Bo’sun whistle started shipping with the Cap’n Crunch cereal box. On the reverse was a comic strip illustration with the Captain repeating the running joke about Seadog using a whistle instead of barking “like other dogs”, and the four-kid crew standing one above the other and holding a whistle on a rope ladder, stating what each would use theirs for. Atop them all was Brunhilde, a German name meaning “ready for battle”, whose speech bubble contained a curious phrase written in all caps: “I’LL USE MY WHISTLE FOR A SECRET CODE!”. The copy describing the prize found inside the box was even more explicit:

Here’s your chance to toot a real whistle just like Seadog uses in all those funny Cap’n Crunch adventure commercials. Once you have mastered its two note tweet-toot you will be able to make up all kinds of secret signals. (emphasis added)

One of those two notes happened to emit the special 2600 Hz tone that phone phreak groups discovered about the toy almost immediately. Given that most of them were teenagers, it’s likely that many grew up eating the cereal and following the cartoons on TV, not to mention the greater appeal for blind children – as many phreaks were – of a toy that produces an audible sound. But, a sound at that specific frequency seems too convenient to chalk up to mere coincidence, especially in light of the attention to detail this particular cereal brand enjoyed from Quaker and Compton executives.

Two years in development at the Arthur D. Little (ADL) consulting firm, where its flavor profile and coating was created by microbiologist Pamela Low and Arthur Little, himself, a renowned chemist from MIT, the cereal’s trademark crunch was the result of market research into what properties of a food most appealed to children under ten. Compton Advertising would incorporate the answer, crunch, into the product name for one of the most expensive marketing campaigns ever to that point, at least for a cereal.

Cap’n Crunch’s development and launch coincided with the start of Project Greenstar, a top secret initiative of Bell Labs to build an electronic toll fraud detection system. The project was funded by its parent company, AT&T, and its first operational unit was installed at the end of 1964. The “big, bulky machines” were designed to spot the unauthorized presence of 2600 Hz on its trunk lines and to automatically record the telephone calls where the anomaly was found.

Six experimental units were deployed in Los Angeles, Miami, New York and New Jersey, where most of the fraudulent activity was known to be taking place. Eventually, the project expanded to surveil over 33 million long-distance phone calls between 1964 and 1970, when the project was discontinued. The public would only find out about it in 1975 as a result of a kickback scandal involving a former company Vice President exploded in the press and the massive surveillance system was uncovered.

At first, the surreptitious phone tapping operation only netted about 25,000 illegal phone calls on the network. That number ballooned to 350,000 in 1966, the very same year Cap’n Crunch’s 2600 Hz whistle was introduced to millions of American children and teenagers. Not long afterwards, a U.S. Air Force radar technician who was plugged into the blind phreaker networks frequented by people like Joe Engressia, heard about the cereal whistle’s useful phreaking properties and decided to adopt the cartoon character’s name as his alias.

John Thomas Draper, a.k.a. Captain Crunch, had been ‘phone phreaking’ across the country since his early twenties in Volkswagen van equipped with telephone switchboard and a “super-sophisticated” computerized medium frequency (M-F) radio transmitter. His adventures and his nickname would become public knowledge in 1971, when budding non-fiction writer Ron Rosenbaum penned an investigative piece for Esquire magazine detailing the exploits of multiple phone phreaks young and old.

Rosenbaum’s article reportedly motivated Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to track down John Draper and his phone phreak community to learn all they could about the “secrets of the little blue box”. Although part of Apple Computer’s ‘origin story’, the pair of future Silicon Valley heavyweights were nevertheless quite late to the party. The blue box was old news to those in the know, like the telephone company and the person Rosenbaum calls “Al Gilbertson”, the device’s ostensible creator.

Will the Real Al Gilbertson Please Stand Up

Al Gilbertson was made up to hide the real identity of the person who invented the blue box, or at least, to whom Rosenbaum attributed its creation. The reality is that by the time the article was written, the list of possible inventors had grown considerably and the idea that a single person would have a clear claim to its invention seemed unlikely, given the nature and purpose of the apparatus.

In addition to Walter Shaw Sr., who was known to be experimenting with tone-based devices early in the 1970s and whose mob ties dovetail perfectly with Gilbertson’s story about a $300,000 deal that fell through with the Las Vegas “syndicate”, other potential candidates can just as easily be tied to Rosembaum’s narrative, which may very well be an amalgam of several people and stories about its genesis.

Professionally manufactured blue boxes had been available in the Southwestern United States since the mid-1960s and for even less than the Vegas mobsters mentioned were supposedly willing to pay years later. The devices were made by Louis G. MacKenzie, a former Army communications officer and electronics engineer in Pasadena, California, who had the credentials to stake his own claim. MacKenzie’s expertise in tone signaling technology was second to none and unlike the throngs of amateurs in the phone phreaking community, he had the technical knowhow required to build a marketable product.

In the late 1950’s, Walt Disney’s research and development arm hired MacKenzie to develop the tone-based remote control system for the theme park’s first animatronic attraction, a dinner show with dancing feathered bird robots called “The Enchanted Tiki Room”. The same year it debuted in 1963, the CBS evening news broadcast an interview with a man warning of a critical flaw in the nation’s telephone system while showcasing a blue box made by his client, MacKenzie. Looking for a nice payday, the military engineer had offered to “fix” the phone company’s problem, oblivious to the efforts already underway at Bell Labs to build a national electronic surveillance dragnet. Ironically, he would be arrestedfor producing and selling them only a few years later.

Meanwhile, a group of “telephone enthusiasts” working at a Navy research lab also located in Pasadena, had designed and built a “suitcase blue box” – a self-contained engineering marvel that included a rotary dial, a keypad, an audio level meter, switches, and an auto dialer carefully assembled inside a large briefcase. The Bond movie-like contraption soon ended up in the hands of a few Harvard students on the other side of the country courtesy of a Bell Labs “security consultant” named Alan Levi Tritter.

Tritter’s name has remained conspicuously absent in the conversation about phone phreaks and hacker culture, despite not only having a real case for being the first ‘phone phreak’ ever, preceding 8-year old Engressia himself, but by a career that placed him at the center of the government’s most sensitive computation and cryptography projects, not to mention his direct involvement in the birth of the data economy at his alma mater, the University of Chicago.

Fat Man and Fly Boys

Alan L. Tritter was no mere telephone company security consultant, to the extent that he was ever one at all. The flamboyant man who liked to refer to himself as “the world’s greatest programmer” on account of his physical girth, was a math prodigy who by age 19 was working at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, a federally funded research facility dedicated to the development of classified communications and radar technology for the U.S. Air Force.

Weighing between 300 and 500 lbs., depending on the source, Tritter’s personality matched his size, and had developed a reputation as a prankster at the lab in Lexington, Massachusetts. According to fellow computer scientist, Joel Moses, Tritter had the habit of tying up the phone lines at Lincoln Labs and disabling the connections between the research lab and the MIT campus before leaving for the day.

Truthfully, the young math wiz had plenty of qualities that would appeal to a company like Bell Labs. Graduating with a degree in mathematics at 17 from the University of Chicago, Tritter spent most of the following two years as a research assistant for the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics working under Roy Radner, who was just then beginning an illustrious career in economics. A student of renowned economist and Cowles Commission director, Jacob Marschak, Radner built on Marschak’s seminal work on information theory and decentralized organizations, going on to make important contributions to the branch of microeconomics and statistical theory of data mining.

In 1954, Tritter and Radner co-authored a Cowles Commission discussion paper titled Communication in Networks, dealing with the different approaches to determining the costs of information exchange. The highly technical draft was part and parcel of the Commission’s central focus on econometrics – the use of statistical and mathematical models to forecast, manage or test economic activity. Generally seen as antagonistic to the Friedman/Hayek school of Austrian economics, Cowles Commission economists were nevertheless at the vanguard of the burgeoning partnership between the finance sector and the defense department’s cutting edge computer technology research.

A watershed moment arrived just before Radner was to begin his participation in the Cowles Commission as a research assistant himself, when the Linear Programming (LP) models developed in the Air Force’s Project SCOOP (Scientific Computation of Optimal Programs) to solve logistical challenges in the military, such as calculating crop rotation, ship routing and even commodity flows in the economy were presented at the Commission’s summer conference of 1949.

Cowles Commission fellows would expand on LP’s applications to resource allocation models as part of a sub-contract with the RAND Corporation. Marschak’s successor, Tjalling Koopmans, moved the Commission’s focus from econometrics to LP marking the introduction of applied mathematicians, such as Tritter into the Commission’s work, which was subsequently fed back into SCOOP by integrating the economists’ mathematical frameworks and computational methods into early computers like the ENIAC and MARK II, as well as the just-released IBM Type 604 electronic punch card calculator.

The Cowles Commission/RAND partnership was a key turning point in post-war economics as LP opened the door to computerized applications of game theory in financial markets and set the stage for the data economy. SCOOP’s top mathematician moved to RAND in 1952 to continue developing these mathematical programming methods, which were simultaneously used to create the nation’s first air defense system at the purpose-built Lincoln Laboratory.

The Semi-Automatic Ground Environment Air Defense System (SAGE) was born after the Air Force, in conjunction with the Los Alamos National Laboratory, British Atomic Energy Authority and the Naval Research Laboratory, reported elevated levels of radioactivity from Scotland to Alaska to Washington, D.C. and a committee convened by celebrated MIT engineer, Vannevar Bush, determined that the Soviet Union had conducted its first nuclear bomb test in August of 1949.

This motivated an MIT physics department professor and member of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) to push for the creation of a ground-based radar system using a digital radar relay technology developed at the Air Force’s Cambridge Research Laboratory, which could convert analog radar signals into digital code transmitted over telephone lines. The only obstacle was finding a computer fast enough to handle real-time data inputs.

Reapers of the Whirlwind

When Tritter first arrived at Lincoln Labs in 1955, on a leave of absence from his Cowles Commission work at the University of Chicago, the mysterious and sudden weight gain he had begun to experience after graduation seemed to be the least of his worries. The FBI had opened an investigation into the now 20-year old young man as a result of an anonymous letter penned by a purported female student of the University of Chicago, accusing Tritter of having Communist affiliations.

Field offices across the country started looking into the claims, interviewing people familiar with those circles. He was eventually cleared of any subversive activity and subsequently contacted by the FBI after the Boston Field Office recommended that he be tapped as an informant. Whether or not Tritter obliged is speculation, but he would have no problem maintaining his staff position carrying out heavily classified work on the air defense system at Lincoln Labs, which had its various research vectors collected under the codename Project Whirlwind.

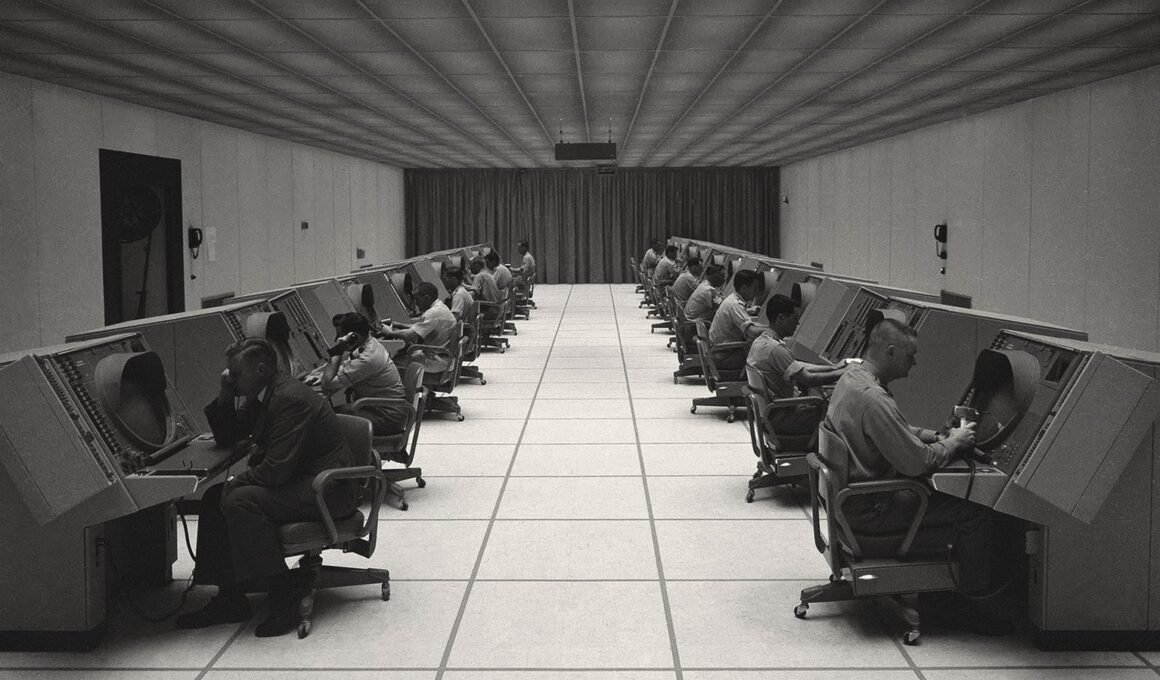

Tritter’s arrival coincided with RAND’s massive contingent of systems engineers, who were tasked with programming the SAGE system. Remaining at Lincoln Labs until at least 1959, Tritter would be privy to the paradigm-shifting transition from vacuum tube computer electronics to the fully transistorized, modern versions. In 1958, once SAGE was fully operational, its research and applications were continued through a spinoff called the MITRE corporation, staffed with 485 Lincoln Lab employees.

However, MITRE was hardly the only digital computing concern that emerged from Lincoln Labs, which in many ways was not just a crash program for the SAGE air defense system and other military applications, but for digital computing technology, in general. Parallel efforts in the private sector were coordinated through the National Joint Computer Committee, a bi-annual and bi-coastal conference organized by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers and the Institute of Radio Engineers, that was inaugurated the same year Lincoln Labs was established.

In 1959, the conference’s 16th edition was held in Boston, Massachusetts. Chaired by Lincoln Lab’s lead engineer for SAGE’s real-time data processing systems, Frank Heart, the event featured a prototype of the Program Data Processor or PDP-1, which had been designed and built by yet another Lincoln Labs alum, Ben Gurley. Hired away from the research facility by the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Gurley took just over three months to complete the construction of the first machine, slated for mass production at an ‘affordable’ price point between $85,000 to $120,000. Gurley’s Lincoln Lab colleague, Ed Fredkin, who by then was working for the legendary father of cybernetics, J. C. R. Licklider at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) convinced his bosses to become the PDP-1’s first customer after seeing the “fantastic” machine at the conference.

Fredkin, a former Air Force fighter pilot, decided to call on John McCarthy to consult for BBN in 1960 and develop McCarthy’s groundbreaking time-sharing ideas on the PDP-1. The project got started between the two of them, with the help of at least one colleague he’d brought along with him from Lincoln Labs, Alan Tritter, joining in one place four pivotal figures in the history of cybernetics. Two of them widely recognized pioneers in their fields, a third, Fredkin, considered somewhat of a wayward genius who nonetheless proved valuable to the designs of the national security state, and Tritter, a virtual unknown with an undiagnosed case of lipoma – a benign tumor that had grown so large, it accounted for a third of his body weight.

After getting into several rows with Licklider over incomplete assignments, BBN’s head of psychoacoustics, engineering psychology, and information systems research started docking his pay until Tritter left to work for Dick Bennett at Data Processing, Inc. Fredkin, unsatisfied with the pace of the projects at BBN decided to pursue earthly riches instead. Licklider soon left the Boston-based consulting firm as well to lead up a new initiative at the Pentagon later renamed ARPANET.

Only McCarthy stuck around BBN to continue working on the time-sharing modifications to the PDP-1, which would come to hold a special place in hacker culture lore as the machine that ran the first multi-user video game, Spacewar! at the department of Artificial Intelligence McCarthy himself would establish at Stanford University. But, hacker culture still didn’t exist as such in the early 1960s and not even the term ‘phone phreak’ had entered colloquial parlance.

That was about to change when Tritter got a hold of the infamous briefcase blue box made by the Navy research lab in Pasadena. Donning his best undercover Bell Labs security consultant shoes, Tritter walked into the life of three unsuspecting Harvard students, and showed off the nifty piece of technology in 1963. After befriending the students and advising them on the technical details of the device and its advantages over the smaller one they had built with cheaper components, Tritter reportedly turned them into the phone company.

Their story was featured in Fortune magazine and Harvard’s school newspaper, The Crimson, but not until several years later in 1966, just as Cap’n Crunch’s whistles began shipping and Bell Lab’s Project Greenstar, by then renamed “Toll Test Unit”, was in full swing. The coverage, which had the FBI painting them as a “spy ring”” has been credited with inspiring the first real wave of ‘phone phreaks’. Around the same time, John Draper returned stateside from his Air Force deployment in the UK to begin his well-equipped sojourn across the country while supporting himself with odd programming jobs here and there.

Tritter traded places with Draper and enrolled at Exeter College at the University of Oxford, laying low across the pond for a few years and working on his dissertation. He would resurface a few years later at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Laboratory working under UC Santa Barbara’s Alan Konheim, once again providing sensitive information to curious researchers. This time to none other than the putative founding father of the cypherpunks and developer of public key cryptography, Whitfield Diffie.