FORT MEADE, MARYLAND – Suspicions of an intelligence agency’s involvement did not deter people like Lazlo Hanyecz and other early Bitcoin adopters, who despite concluding that Satoshi was “not a real person” after communicating directly with the furtive cryptocurrency genius, continued to work on the protocol as one the project’s core programmers. Hanyecz would later be credited with setting up the first “real-world” bitcoin transaction as the proof-of-work crypto neared its debut on the world stage.

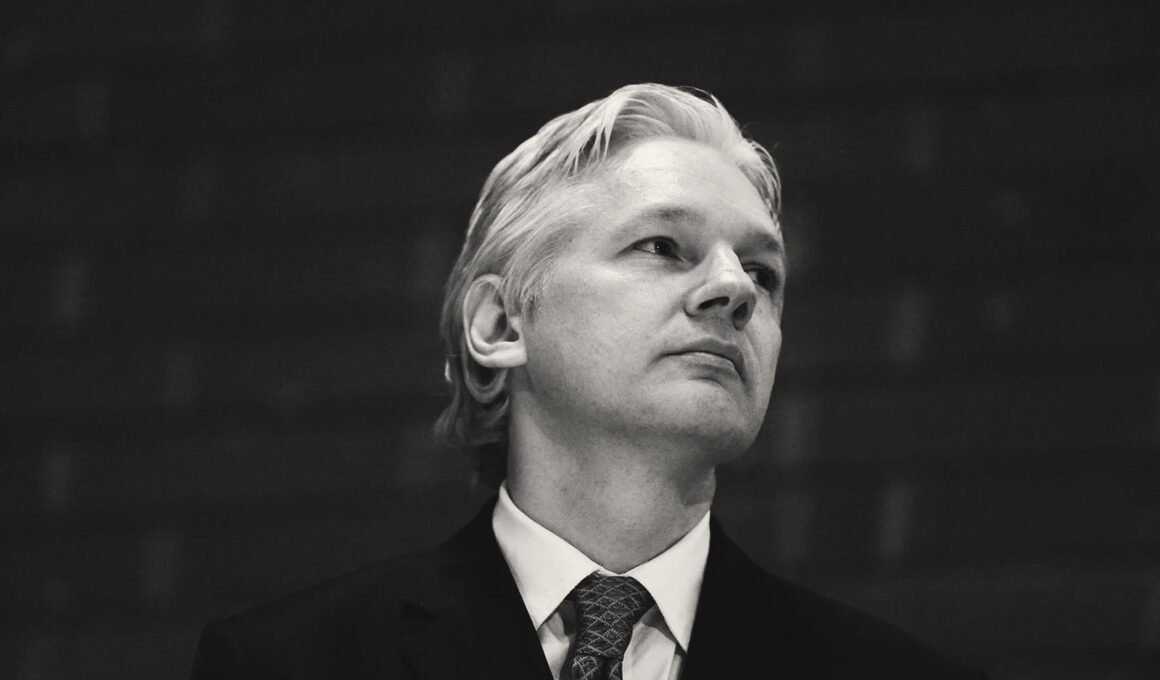

Bitcoin’s political destiny was precipitated by events taking place within the hacker community it came from. Almost two years after the whitepaper’s publication on the Bitcointalk forum, PayPal’s decision to freeze the account of the Wau Holland Foundation, a German non-profit entity which had been processing donations for WikiLeaks since 2009, prompted a call from members of the cypherpunk listserv – including Julian Assange –, to make Bitcoin donations available to the outfit directly.

The suggestion garnered “uncharacteristic” opposition from Nakamoto, leading to acrimonious debate on the electronic forum. According to the discussions, Satoshi was afraid that making such a splashy entrance would bring on problems “likely [to] destroy [Bitcoin] at this stage”. However, the community prevailed and Nakamoto made a quick and dramatic exit from the project altogether.

Following his final disappearing act, the contours of the cryptocurrency ecosystem began to take shape early in 2011, a watershed year for Bitcoin. The first crypto exchange started operations; Ross Ulbricht’s infamous Silk Road marketplace went online, and towards the end of the year, a media organization affiliated with Occupy Wall Street (OWS) received the first donations of the peer-to-peer digital token, which was described as the “perfect overlap of ideology and functionality”.

This “perfect overlap” took decades to achieve, and involved the participation of post-war social scientists, electrical engineers, and economists, who built the philosophical and early technical underpinnings of cybernetics, through the rise of cryptography as a mainstay of signals intelligence and international banking, down to the neo-technocratic, Hayekian cultists, who saw fit to seize upon the nation’s real class and social divide to apply an ideological veneer over a ‘virtual’ currency that could serve their class interests in a future technological utopia.

Satoshi’s timely departure provided a measure of the “appropriate theatricality” needed to foster the adoption of digital cash in general, as suggested in some of the earliest cypherpunk threads. But, no amount of drama would have been effective without an audience to sit through the show, which by then comprised hundreds of thousands of people around the world groomed for a life mediated by machines through a steady diet of hacker conferences, targeted publications and politically-charged acts of ‘hacktivism’.

Knights of the Red Square Table

Five days after the first “hacker conference” was held in San Francisco, California, a group calling themselves the Chaos Computer Club (CCC) surreptitiously wired 134,694.70 Deutsche Marks (about $135,000 today) to their own bank account in an electronic heist that would send shockwaves through the German banking industry and launch the international hacktivist movement.

Known as the BTX-hack, CCC founders Herwart “Wau” Holland and Klaus Schleisiek carried out the digital robbery between November 16 and 17, 1984, accessing the servers of the Sparkasse bank in Hamburg, Germany, through their own account in the free public savings institution and running a malware program for thirteen hours without detection. On Monday, November 19, the pair of pseudo-cyber criminals called a press conference to reveal their deed as a warning of the inherent security vulnerabilities of computer networks and promptly returned the money.

Reportedly motivated by the West German government’s intention to develop “machine-readable ID cards” a year before through a new census law, Wau, Klaus and their coterie decided to send a message to German authorities – first with a mere warning to the state-owned telecommunications company about the weaknesses in the BTX system, followed by the infamous cyber security spectacle, which afforded them the opportunity to bring the concept of “hacker ethics” to large numbers of European youth for the first time.

Although the census legislation had been approved without controversy in March of 1982 with the arrival of Helmut Kohl’s first coalition government, an unexpected wave of protests against the law erupted early in 1983, spurring nationwide boycotts and a deliberate campaign by both liberal and conservative party members to block its implementation via the court system. The country’s Federal Constitutional Court issued a temporary injunction to the complete surprise of the Kohl government, ruling that the census law “violated the right to privacy, […] implicit in the country’s constitutional commitment to human dignity and the free development of the individual personality.”

Privacy was thus born as one of the “central political issues of the 1980s and beyond”, revolving specifically around the burgeoning digital technologies. “Hacker” culture’s political impetus was to be constructed around this central premise and fostered by the elders of the computer counterculture movement, like Wau and Klaus, whose hacker collective had begun in 1981 at the West Berlin offices of the radical leftist newspaper, Die Tageszeitung, where they had placed an advertisement calling all Komputerfrieks to join them for their first informal meetings around Germany’s most “political table”.

Stretching five and a half meters long and one and half meters wide, the wooden piece of furniture had been purchased for 800 marks in 1969 at a thrift store in Berlin by Hans-Christian Ströbele – future founding member of the Green Party – and Klaus Esche, who at the time were both part of the “Socialist Lawyers Collective”, a legal defense team also founded by Ströbele to defend terrorist militants of the Red Army Faction (RAF) and student activists.

Ströbele, putative founding member of Die Tageszeitung, transferred the table to the newspaper’s headquarters in 1979 after he had reclaimed it from the theatrical activists who had ‘stolen’ the table not long after he had purchased it for the offices of the Socialist Lawyers Collective. The thieves were part of a communal living project called Kommune 1 (K1), which engaged in provocative, satirical protest actions like those performed concurrently by the YIPPIES in the United States, who would also play a vital role in recruiting new generations into the what a Florida-based art collective uncritically, yet precisely, characterized as “a strategic move away from the streets towards the online”.

Hold the Line

Abbie Hoffman’s YIPPIES had largely disintegrated by the early 1970s, but followers were kept engaged through its Youth International Party Line newsletter, which continued on as the “Technological Assistance Program” or TAP. The newsletter had been a phone phreak recruitment tool since inception – Hoffman himself was an avid phreaker –, regularly publishing phone phreaking guides and generally encouraged the use of new technologies as a vehicle for creative civil disobedience, as many of the countercultural organizations in Europe and the UK were doing, as well.

TAP was edited by Richard Cheshire, a.k.a. Cheshire Catalyst, one of the anonymous phone phreaks mentioned in Ron Rosenbaum’s seminal article, Secrets of the Little Blue Box. Cheshire, who became one of the mainstay guest speakers at hacker conferences along with Draper, had reportedly “wandered into” the ARPANET network at some point in the late 70s or early 80s while on a lunch break from his Manhattan job and discovered that he could access Soviet nuclear test data from a Norwegian seismic station connected to the network.

The expert hacker convened a special phreak conference at the D.C. Gramercy Inn in 1980, to address the network’s security flaws, ostensibly out of a sense of patriotic duty. Attended by 100 or so people, the guest list remains a mystery, but more than likely included members of the Homebrew Computer Club, like Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs and Captain Crunch, all of whom were by then well acquainted with each other. In the Technology Illustrated article that reported this event, Cheshire hints at the presence of military or intelligence personnel in the audience, and although his actual line of work is never disclosed, his own employer seemed to require unofficial access to Cheshire Cat’s special skillset.

Soon after this conference, Jane Fonda’s movie company, IPC Films, approached Rolling Stone contributing editor Steven Levy to write a story about computer hackers. The studio’s development director happened to be a former colleague of Levy’s wife at the Village Voice and thought the Penn State English major would be a good fit for the piece, which would then be used to “pre-option” it for a movie. After publication, Levy accompanied her and film producer, Bruce Gilbert, to visit Marvin Minsky at MIT’s AI lab “to figure out how we might make a movie out of this”.

Meanwhile, at Xerox PARC in Palo Alto, a group of computer scientists together with colleagues from nearby Stanford University started running a computer message board exploring the social and civic role of computation, specifically around military uses. Initially focused on “computer-aided nuclear war”, the discussions were technical in nature at first, but with the launch of Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a.k.a. “Star Wars” in 1983, the dialogue began to acquire a political dimension.

The Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility (CPSR) was the non-profit organization that emerged out of this message board, and would play a pivotal role in framing the political dimensions of cyberspace. Nuclear war was the single greatest cause used to align the political views of many of the counterculture after Vietnam and many, if not all of the leaders of the early phone phreak-cum-computer hacker community, embraced notions of globalism as espoused in Buckminster Fuller’s ideas about ‘spaceship earth’ to arrive at a solution to the problem.

After IPC’s movie project was nixed, Levy switched to authoring a full-fledged book titled “Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution”, which was published in 1984 and is said to have inspired the first hacker conference that same year in California, which was organized by Stewart Brand, founder of Whole Earth Catalog magazine, heavily influenced by Fuller’s “World Game” approach to solving planetary issues through technology, and one of the first publications promoting the idea of ‘green’ technologies.

Stanford graduate, Brand, had run Whole Earth out of the Project One warehouse community in San Francisco during the height of the counterculture and was one of its latter-day icons. Together with his associates at the Point Foundation, Brand brought together all of the top proto-hackers of his generation – Phone Phreak superstars like USAF service member John Draper, a.k.a. Captain Crunch, Cheshire Catalyst, and many others to educate the new generation and complete the transition from “counterculture to cyberculture“.

Later that winter in West Berlin, on the heels of its spectacular media coup, the CCC organized Europe’s first hacker conference in December, 1984. Many of these networks would work together over the following years to organize a global hacker movement through conferences and publications targeting the young, impressionable minds who had been born into the digital age. In 1989, the first truly international hacker conference took place in Amsterdam, issuing the first hacker manifesto, an 11-point resolution delineating the duties and ethical obligations of “planetary citizens” concerned with the free flow of data in democratic societies.

What Do They Call a Whopper in Amsterdam?

Organized by the neophyte publishers of a Dutch hacker magazine called Hack-Tic, in close cooperation with the CCC and popular American hacker publication, 2600, the Galactic Hacker Party was held at a former church building, repurposed as an entertainment center in the 1960s and since known as an iconic symbol of the counterculture called Paradiso. Taking place in the fall, it would be the first time computer hackers from different parts of the world would hold panel sessions to discuss and lecture attendees about the state of hacking.

Access to the venue was facilitated by Michael Poleman, the Dutch representative of an international coalition of civil society groups – a.k.a. NGOs –, called INTERDOC that sought to place emergent information technologies at the service of social justice issues and economic development in third world countries, which was also the stated goal of the conference itself. INTERDOC was funded by the Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to experiment with a transnational computer network for NGOs.

A Canadian Crown company, the IDRC was established in 1970 following a recommendation by the Pearson Commission, a UK-sponsored panel of economists tasked with conjuring up the justifications for a recalibration of the development finance regime on behalf of the Anglo-American establishment on the eve of post-Bretton Woods floating currency system and the concurrent digitalization of the world’s financial infrastructure.

Indeed, the event was specifically intended to contribute to the proceedings then taking place at the United Nations about information flows in the lead up to the creation of the sustainable development goals (SDG), which are part and parcel of the revamped development finance regime. Speakers included MIT professor and “father of artificial intelligence” Joseph Weizenbaum, and Community Memory developer Lee Felsenstein.

Perennial hacker conference attractions like Captain Crunch were also present, as were CCC’s BTX-hack veterans, who by then had gained worldwide notoriety after hacking a computer at NASA on its way to becoming Europe’s largest “white-hat” hacker association, going on to perform cyberattacks on CERN and the French atomic energy commission, among many others to help corporate, public and academic entities patch security deficiencies in their computer systems.

Network connectivity for the historic meeting was handled through the Dutch National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science (CWI), birthplace of the “European Internet“, conceived when a hole was drilledfrom the Dutch National Institute for Nuclear Physics (NIKHEF) building next door through the wall to run a cable into the CWI’s computer sciences department, inaugurating the first node of what would become the Old World’s Internet system and the first root domain outside the United States.

Some of the first NGO digital bulletin boards like PeaceNet and GreenNet were hosted on CWI servers and operated by INTERDOC’s Dutch affiliate, Poleman. These boards were part of the international networks of NGOs running through the United States, England and Europe. Communications between organizations like the CPSR and INTERDOC signatories shaped the political agenda of conferences like Galactic Hacker Party and other technology-driven activist initiatives.

Not far from the room where CWI’s servers hummed was David Chaum’s office, the so-called “Godfather of cryptocurrency” (to distinguish him from Whitfield Diffie), who headed its cryptography department since 1982. In 1989, just as the Galactic Hacker Party was about to get underway, he incorporated a company called Digi-Cash in The Netherlands, which intended to market the digital currency system he had developed from his 1979 dissertation at UC Berkeley.

Chaum’s innovation attracted considerable attention from Credit Suisse, Visa and Microsoft more than a decade before what we call cryptocurrency made its first appearance. Piloted by Deutsche Bank and on 10,000 clients of a bank in St. Louis, Missouri, in the mid-90s, Chaum’s method was on the verge of becoming the standard in digital cash. But the world wasn’t ready for the “blind signature” authentication model that would prove integral to the design of cryptocurrency and Bitcoin, in particular.

The digital marketplace didn’t exist yet and the consumer class for that new modality of commerce was still being groomed to participate in a brave new world, where digital soap boxes would try to replace the town square and DDoS attacks would try to supplant civil disobedience in the flesh. The CCC’s membership had grown considerably by the end of the decade, not to mention some of the other, even older computer clubs which had furnished most of the audiences for these early conferences.

On the Cusp of the Data Economy

The Berlin Wall would come down just three months after the self-styled Galactics vowed to make the “protection of individual liberties” their “paramount concern”, emphasizing that “no private information shall be stored and retrieved by electronic means.” Among the adopters was a recent new member of the CCC, Andy Müller-Maguhn, an eighteen-year-old activist who would become the organization’s long-time board member, spokesman and Europe’s honorary ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) representative.

In 2007, Müller-Maguhn would meet a computer hacker at a CCC event in the German capital by the name of Julian Assange, and would become the Wikileaks founder’s benefactor and a central figure in the rise of the controversial Australian. Müller-Maguhn would spark a controversy himself in 2011, when he was voted off the board of the CCC over his decision to expel whistleblower Daniel Domscheit-Berg from the club, after he had started a separate information leak organization to rival Wikileaks, called OpenLeaks.

Domscheit-Berg’s outfit debuted just before the Wau Holland Foundation, where Müller-Maguhn has been Vice President since 2012, began taking Bitcoin donations on behalf of Julian Assange’s organization. The foundation also runs the AssangeDAO (decentralized autonomous organization), an ETH token to raise money for Assange’s legal defense. At the bottom of the AssangeDAO website, a disclaimer warns potential buyers of the “cross-border collective” token that the organizers assume “no liability for [financial] losses arising out of or in connection with” their participation, ending with a prompt to “do your own research”.

Research, in this case, only applies to information about your monetary investment, ironically marketed through the claim at the top of the website assuring us that Julian Assange “faces 175 years in prison for publishing truthful information”. We are thus presented with two kinds of information; one that has direct value to you as an investor in a scheme that promises a return and another, essentially worthless appeal to your sense of $JUSTICE – as the token itself is named – to get you to buy in.