LONDON, ENGLAND – Boasting three quarters of a century of “investing for development”, British International Investment recently unveiled its new name along with a five-year plan to pour billions of pounds into technology, climate and “inclusive finance” projects across Africa, South East Asia, and the Caribbean.

Thick layers of marketing copy peddle the familiar themes of hyper optimistic innovation and economic growth so commonplace in 21st century corporate literature. From the document’s executive summary to its conclusion, the cheery, calculated vacantness of each paragraph leaves us with a sense of a promise waiting to be broken.

British International’s CEO, Nick O’Donohoe, peppers his foreword with key buzzwords like “green, renewable” and “sustainable” or “inclusive”. As the co-founder of Big Society Capital (BSC) with Sir Ronald Cohen, O’Donohoe can claim to be one of the originators of this new ‘conscious’ capitalist lingo. BSC was the world’s very first venture capital firm dedicated exclusively to funding startups focused on social impact, and emerged out of the UK government’s own initiatives to foster this space.

Now, the former Colonial Development Corporation (CDC), as British International Investment was once called, has become the UK’s primary vehicle for the propagation of the impact finance model. Repeatedly referring to itself as “the impact investor” in the paper, the wholly-owned property of the UK government estimates that £5 to £6 Billion will be invested throughout the Commonwealth over the next five years, and Africa in particular.

British International, O’Donohoe writes, will be “one of the world’s largest climate investors in Africa” as well as offering “radical solutions to global challenges” faced by the economies on the continent by investing in “financial digital transformation” projects and “technology-based businesses”. A recent Tech Crunch article lists some of the earliest recipients of the Crown’s largesse, which include several private equity firms, fintech and smart infrastructure startups based in Africa, but controlled by Western European or American concerns.

Perhaps the most noteworthy is British International’s continuing investment the Energy Access Relief Fund (EARF), a public-private partnership revolving around massive hydroelectric projects in Africa between the Shell Foundation, The Rockefeller Foundation, World Bank, International Finance Corporation, USAID and many others. Their involvement in EARF precedes British International’s fresh rebranding and in many ways feels like a reprising of the institutions and relationships that were integral to its formation seventy-five years ago.

Before launching into a more in-depth exploration of British International’s current portfolio and the people who are leading the merger of development finance with impact finance, it behooves us to take a journey into the origins of this organization, the nature of so-called development finance and Western capital’s undying and violent obsession with Africa.

Introduction

In the paragraphs and pages that follow, the impetus driving the aid and development finance paradigm embodied by British International Investment and other development agencies will be explored through an unorthodox interpretation of the Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, positing that the conflict was a deliberately orchestrated public ritual of death and suffering, executed at the highest levels of the Anglo-American establishment, in concert with the Catholic Church and other religious entities to rescue a failing hegemonic project in the second half of the twentieth century.

Unable to maintain the post-war international monetary policy established after the war, the best laid plans of the Western liberal order were beginning to crumble under their own weight. Cold War rhetoric was hardly enough to convince France and Germany to keep their dollar reserves and the promises made by the industrial elites and their bankers to rebuild the world had run aground at the Suez Canal.

Development was associated with reconstruction and rebuilding what the war had destroyed, and therefore temporary. A new, more permanent project had to be found, dug up or invented so that the economic daisy-chain would not be broken and the colonial tethers could remain invisibly in place. The solution was poverty and all the social ills caused by the condition that only the wealthy can address and, crucially, also create.

The African continent, so vast and full of riches, was the cornerstone of Cecil Rhodes’ deranged plan to restore the British Empire to its former glory. His colonial madness infected a whole generation of fellow countrymen and Anglophiles across the pond and around the world who would work towards a similar end, rebranding their neo-colonial visions with eco-friendly, social justice themes to better conceal their relentless quest for economic, social and spiritual domination.

Replenishing the Queen’s Coffers

The creation of the Colonial Development Corporation in 1947 had been preceded by rumblings in the UK Parliament about the Colonial Office’s neglect of the far flung territories held by the Crown, which had seen a spike in “disturbances” and riots as a result of the economic hardships of the Great Depression.

A Commission formed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Malcom MacDonald, in 1938 to investigate conditions in the West Indies confirmed “the low standard of living [..] and the extent of the poverty and ill health that exist in them” and served as the political impetus for the beginnings of a long-term Colonial development policy.

Her Majesty’s Government (HMG) was also facing pressure from a growing unease in society at large regarding colonialism itself, further compounded by Germany’s demand that the UK return its colonies in East Africa – placed under British mandate after Versailles –, leading to what was dubbed in those days as the “Colonial Question“.

However, the real inflection point only arrived after the war, when the Queen’s coffers were running dangerously low and food and raw material shortages threatened the British Isles themselves. Suddenly, addressing the issues faced by the colonies became a top priority, and the post-war Labour government of Clement Attlee placed ‘decolonization’ at the top of its agenda, led by his foreign minister, Ernest Bevin.

Appealing to the political sensitivities of the working classes that voted them into power, the Attlee administration leaned into the anti-colonial messaging, with an official party hand-out distributed in the summer of 1946 going as far as declaring that “British Imperialism” was dead. Just after the creation of the CDC, Attlee’s Cabinet Secretary, Sir Norman Brook, summarized the propagandistic “conundrum” posed by the hastily-established agency in reference to Africa, specifically:

“At recent meetings there has been general support for the view that the development of Africa’s economic resources should be pushed forward rapidly in order to support the political and economic position of the United Kingdom… [This policy] could, I suppose, be said to fall within the ordinary definition of ‘Imperialism’. And, at the level of a political broadcast, it might be represented as a policy of exploiting native peoples in order to support the standards of living of the workers in this country.”

Brook went on to warn Attlee that if the policy were to be “disclosed incautiously or incidentally without proper justification and explanation”, the political ramifications would be grave. Fully aware that the very survival of the British pound was riding on the successful implementation of the new policy, Brook thus offered a solution that has come to characterize international aid and development policies ever since:

“It can, of course, be argued that the more rapid development of Africa’s resources will bring social and economic advantages to the native peoples in addition to buttressing the political and economic influence of the United Kingdom.”

It is at this point when arbitrary concepts like the “Third World” or “developing” nations begin to take hold of international economic discourse and the tarnished vocabulary of Colonialism starts to recede into the background, and British Colonial territories are rebranded as the Commonwealth of Nations. Even the development finance agency’s acronym was quickly substituted for the new terminology, becoming the Commonwealth Development Corporation, instead.

Britain itself was in a period of transition, as the barely-concluded Bretton Woods conference ushered in the pillars of a new Atlanticist order through the establishment of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, more widely known as the World Bank. Attlee’s promise to “recapture Britain’s economic independence” by exploiting its colonial properties was critical to maintain its balance of payments in the face of the new dollar standard.

As Brook counseled, Attlee’s government continued to shape the narrative through the lens of decolonization while the real work went on behind the scenes. Bevin’s close advisor and Toynbee protégé, Sir Harold Beeley, worked side by side with OSS agent and head of the American intelligence outfit’s Africa Research Section, Ralph Bunche, to incorporate these neo-colonial economic concepts into the structure of the recently-created UN.

Beeley, a high-level UK intelligence asset since the late 1920s, had been in charge of the Palestine desk for Toynbee’s Foreign Research and Press Service during the war, and was a critical figure in the subsequent economic transition of the region as the British Mandate was partitioned into their ‘decolonized’ borders. As Chairman of the Anglo-American inquiry on Palestine, Beeley was also highly instrumental in the creation of the Zionist state, and was the invisible hand behind Bevin’s secret policy decision to allow Transjordan’s annexation of British Palestine, described by some as the “malevolent midwife at the birth of the state” of Israel.

Central to these machinations was the imperative to retain control of the oil reserves in the Middle East and North Africa, which held the key to post-war Western hegemony. Other parts of the African continent had yet to feel the brunt of the “oil curse”, as some disingenuously term the socio-economic effects, that deliberate acts of sabotage, political manipulation and blackmail employed by powerful energy interests and their state level accomplices, invariably have on the populations unlucky enough to live near the valuable resource.

That would change in 1956, when the Royal Dutch Shell Company, then operating as Shell D’Arcy, struck oil in the eastern part of Nigeria. Within less than a decade, American, French and Italian oil companies would also start operations in West Africa, setting the stage for one of the most brutal conflicts the world has ever known and the first steps of the impact finance regime.

Subject to British rule since 1884, the independent Federal Republic of Nigeria wasn’t officially established until 1963. Guided by the colonial power, a federation was created from three distinct peoples – the Muslims in the North, the Yoruba in the Southwest, and the Igbo in the Southeast –, in a pattern repeated throughout the process of ‘decolonization’, where ethno-geographical divides were artificially confined within the same borders to make intrinsically unstable countries. Often excused as a way to encourage “regional and ethnic competition”, this strategy was pursued in order to facilitate the imposition of economic policies, preserving colonial interests without the formal colonial status.

Barely a year into the uneasy union, crude outputs skyrocketed from 84,000 barrels a day to more than 300,000 by 1965, making Nigeria one of the world’s top oil producers. Crucially, over 90% of this production flowed out of the southeastern region, home to the Igbo people and other minority ethnicities whose links to the northern elites that controlled the federal entity in Lagos were tenuous, at best. Once the black gold drew the likes of Gulf Oil, Mobil, and other foreign multinationals to the region, the built-in factional politics would be exploited to serve their interests.

As part of their standard operating procedure, not only in West Africa but elsewhere, the oil companies deliberately withheld production data from the Nigerian government, forcing state officials to “guess the contributions oil revenues would make to Nigeria’s exports and capital flows, as well as their implications for the Nigerian pricing system.” This allowed them to manage global supply and strengthen their pricing cartel.

Nigeria’s oil boom also brought the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to its shores, which monitored the political and economic landscape in the young nation as the savvier and much older countries in North Africa leveraged their oil riches through the recently-formed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) against the neo-colonial incursions of the West.

Panic was setting in at the offices of the Seven Sisters cartel as OPEC’s new tax scheme, compelling oil companies to calculate their tax obligations on the ‘posted’ price of oil, rather than the often lower price of sale was made law in Libya and threatened to spread like wildfire in both OPEC-member and non-member nations. Towards the end of 1965, a draft version of Nigeria’s Libyan-style Petroleum Profits Tax Ordinance began circulating in Lagos, galvanizing the foreign oil interests who began a vicious campaign to try and kill the proposed legislation.

Intense lobbying against the bill was accompanied by the publication of pseudonymous articles in the Nigerian press, warning that the new tax laws would “lead to the closure of many oil wells, accelerate unemployment difficulties, [and] create unrest”, among other dire and thinly-veiled threats. Initially blamed on the U.S. Embassy by the British, the fake articles were eventually traced to Chicago-based Tenneco – one of the many oil concerns operating in Nigeria.

Meanwhile, the CIA was keeping tabs on the developments and warning of the coming instability due to the “rapidly increasing importance” of the tax revenues that the agency projected would more than double in just one year. In 1966, USAID – America’s own development agency and notorious CIA cutout –, commissioned a report to assess the impact that increased oil revenues were having in Nigeria. Titled “Nigeria – A Tiger in Their Tank”, the study found evidence that the oil companies were severely underreporting oil revenues to the Nigerian government. Deemed too “explosive” for consumption by Nigerian officials, the report never left the U.S. Embassy. By March of that year, the CIA was already predicting civil war.

Set Up to Fail

The flash point occurred in the first week of January, 1967, after a British-brokered meeting in Aburi, Ghana, between Nigeria’s Supreme Commander and head of state, Yakubu Gowon, and the governor of the oil-rich Eastern region, Lt. Col. Emeka Ojukwu – the illegitimate, Oxford-educated son of a Nigerian millionaire who had served on the board of directors of Royal Dutch Shell. Gowon had come to power just six months earlier as a result of a counter-coup against another military putschist from the oil-rich Eastern region, Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, a.k.a. Johnny Ironside.

Ojukwu, who would later confess to have masterminded Ironside’s ill-fated decision to assume power after the first coup in 1966 according to the West African correspondent of a German public broadcasting station, was not ready to let this new opportunity pass through his fingers and presented his demands for full autonomy of the Eastern region. To everyone’s surprise, Gowon seemed amenable to the idea and the meeting ended with the expectation of Ojukwu’s wishes being granted.

Objections arose immediately from the British High Commissioner in Lagos, David Hunt, who counseled against acceding to the de facto confederacy, echoing the concerns of some of Gowon’s own inner circle. Gowon, however, seemed intent on ameliorating the escalating ethnic violence that had gripped the young nation since inception and considered that loosening the federal entity’s grip would go a long way towards that end.

Ojukwu’s good will was tested immediately as Gowon promulgated Decree No. 8, fulfilling almost 95% of the Aburi Accord, with the notable exception of the Eastern governor’s secession clause – a meaningless omission, since most believed the decree’s implementation would materially dissolve the federal union anyway. The Eastern governor signaled his true intentions by rejecting the compromise, and moved to stage a nine-month standoff, which led to the formal creation of the secessionist state of Biafra.

Aburi seems to have been nothing more than a bit of theater for an event that had been months, or perhaps years, in the making. Up until two days before the first coup of 1966 took place, Ojukwu was completing his studies at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in the UK, an elite military boarding school for future British Army officers, particularly foreign cadets who make up the military brass of the post-colonial territories of the Commonwealth, not to mention its long list of graduates from the Gulf states.

Nigerians remain divided about Ojukwu’s myth and legend. Many still believe he was a heroic freedom fighter intent on forging a Pan-Nigerian state, and rectifying what he called the “temporary mistake” of regionalization. Others contend he was a malcontent bastard child, who harbored megalomaniacal ambitions rooted in a futile quest for his father’s approval. The truth, as usual, is somewhere in the middle. But it also misses critical parts of the story; namely the strong gravitational pull of the geopolitical forces exerting their indirect, and sometimes direct influence over the course of tragic events that would follow.

In the spring of 1966, Ojukwu divided the Eastern region into separate provinces during Johnny Ironside’s short-lived reign. This move, alone, undermines his claims of working towards a Pan-Nigerian future. Additionally, suspicions that Ojukwu was more than likely working with Royal Dutch Shell behind the scenes were given credence by the Provincial Edict of June 1, 1967, a law passed by the newly-established government of Biafra, which provided the legal basis for accruing oil royalties from the British concern.

Considering that Shell held the rights to over 80% of all crude extraction in Nigeria, (70% of it emanating from the region controlled by Ojukwu), a secret American cable sent over a month later reporting that Shell was convinced that “Biafra was here to stay and that Ojukwu would be kind to the company”, suggests that there was some kind of understanding between the rebel leader and the oil company. In fact, Ojukwu seemed just as confident about his staying power, laughing at the prospect of the Nigerian Navy launching a seaborne blockade of Biafra.

According to the American Consul in Enugu, Bob Barnard, Ojukwu was amused by the notion of Gowon’s naval forces being able to manage Biafra’s “winding creeks and primordial mangrove swamp”. Just weeks into the war, on July 27, Ojukwu would get a major wake-up call when the Nigerian Navy completed a successful amphibious attack to secure 16 storage tanks holding 3.9 million liters (approximately 24.5 thousand barrels) of crude in the coastal town of Bonny and proceeded to surround the fledgling state.

Biafra: Banking on Starvation

From this point forward, the schizophrenic approach of the British and U.S. governments, as well as their proxy international entities, to the tragedy that would unfold over the next three years in West Africa has given rise to numerous theories about the true nature of the Nigerian civil war and the blockade that produced what is thought to be one of the most horrific man-induced famines in history. Publicly, the official stances of the UK and US straddled the line between neutrality and supporting the national integrity of the Nigerian federal government (FMG).

On the other hand, large networks of foreign nationals from the UK, US and other Western countries tied to the Catholic Church and other institutions with proximity to power already present prior to the break out of hostilities were operating on the Biafran side of the conflict, flanked by a worldwide publicity campaign carried out by a PR firm in Geneva, Switzerland, owned by former Madison Avenue advertising executive, H. William Bernhardt, hired by Ojukwu’s representatives four months after the war began.

The Nigeria-Biafra war would become the first televised war in history, even before Walter Cronkite aired his famous report from Vietnam on CBS, and counted with a round-the-clock staff of copywriters and ad men churning out propaganda, which was delivered to every major news agency around the world, including all the top news editors in Western Europe and every member of the British Parliament.

Daily pro-Biafran “war communiques” prepared by the American-owned outfit prominently displaying the official-sounding brand “Markpress News Feature Service” on the letterhead, were printed at the astonishing rate of 7,000 press releases per hour. Bernhardt’s company also assumed the cost of war correspondent’s travel to Biafra, which was organized through the Vatican-based aid and development organization CARITAS.

The members of the press were first flown to CARITAS’ offices in Lisbon, Portugal, then ruled by clerical fascist dictator, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. Once there, correspondents awaited further instructions from Ojukwu’s proxies before boarding a stripped-down and unmarked Lockheed aircraft, one of Bernhardt’s other clients, for their journey to Africa. Packed into the plane’s fuselage were boxes of arms and ammunition destined for the secessionist forces.

CARITAS Internationalis was already a major presence in Eastern Nigeria, along with other Catholic organizations, long before the war. In fact, Eastern Nigeria had over 420 foreign Catholic priests working on missionary projects by 1965. Bernhardt’s original framing of the conflict as a David-and-Goliath struggle against an oppressive and tyrannical foe, would be tweaked about a year into the war and changed to portray the conflict as an “attempt to extinguish Catholic Igbos through starvation”.

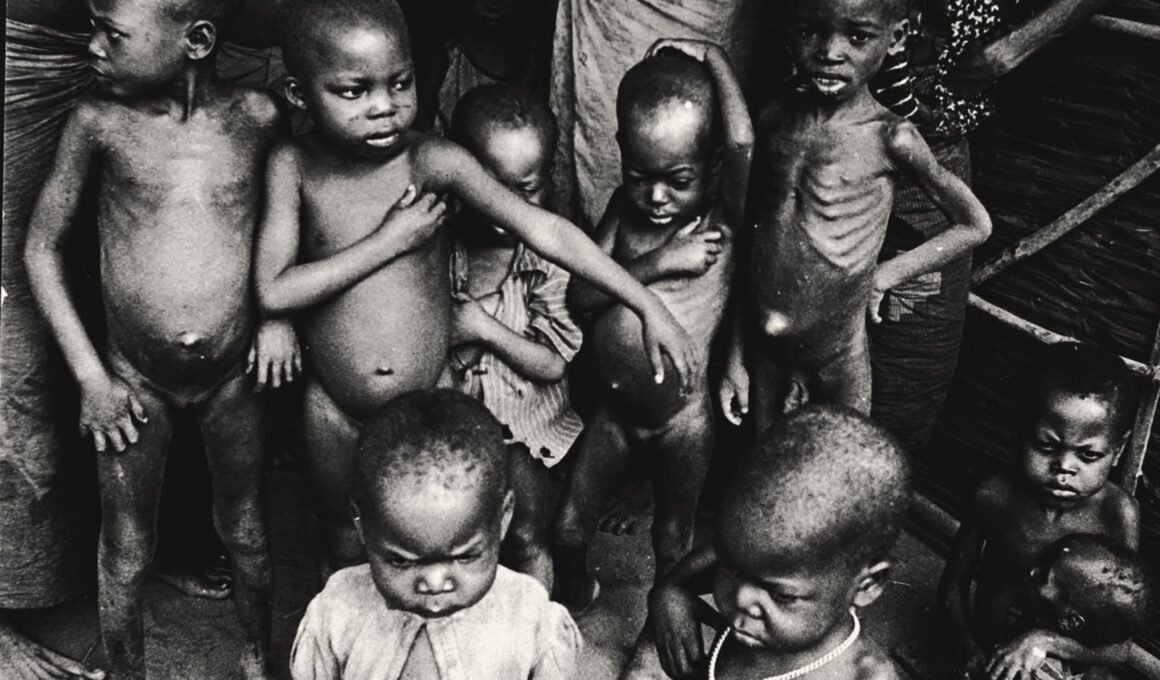

The shift proved highly effective and, in addition to promptly securing the backing of Senator Ted Kennedy, who would become one of the leading supporters of the Biafran cause in the U.S. government, the stories – now featuring searing images of famished African babies –, began getting much more traction in the international press. By August, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix and self-proclaimed MK-ULTRA survivor Joan Baez were holding a Biafra benefit concert in Manhattan, a format that would be repeated by other artists and help make Biafra a global media phenomenon.

Development’s Martyrs

Heart wrenching pictures of starving children in West Africa, with bloated bellies and lifeless eyes was a powerful motivator. In the spring of 1968, Tanzania became the first country to announce a ban on arms shipments to the FMG, followed by a handful of neighboring African countries, and eventually, France, Poland and Czechoslovakia, buttressing Bernhardt’s claims about the propaganda campaign’s goal to stop arms from reaching the FMG.

The obvious skepticism elicited by “news reports” fashioned in an advertising agency was reinforced by an infamous indiscretion made by Father Kevin Doheny, an Irish Catholic priest, who was Ojukwu’s chief of intelligence and managed all radio communications in Biafra, according to US sources. Moving to West Africa just one year after he was ordained priest in Dublin, Ireland, in 1954, Doheny also had links to the international Catholic community through John F. Kennedy’s spiritual advisor, the Archbishop of Boston Cardinal Cushing, and was a blood relative of then US Senator Mansfield (D-MT).

Traveling to Geneva to meet with the US relief representative in 1969, Doheny let slip that although the much-publicized charges of genocide were “highly exaggerated”, they were necessary for the war’s continuation. Such an explosive statement would not have come as a surprise to educated Nigerians, who largely suspected that the “humanitarian outcry about the Nigerian situation cloaks sinister ‘neo-colonial’ maneuvers”, as observed by American officials in Lagos at the time. The war propaganda was not directed at them, after all.

Doheny was only one of many priests and church group members operating on the ground in Biafra. Ojukwu’s entire war effort was being brokered through Catholic and Protestant organizations, which not only executed the humanitarian relief actions, but also served as the main conduit for arms and munitions coming in from different parts of the world, working with the mercenaries hired by Ojukwu.

Practically every airlift carrying food and medicines to Biafra also brought weapons and military supplies. Another group of Irish Catholic priests running one of the food programs in Biafra, called African Concern, often let arms and munitions share cargo space on the planes delivering desperately needed protein and drugs to ill and starving West Africans. Other church groups leased planes from an American front company called Arco, that also smuggled weapons into Biafra, and was operated by American gunrunner, Hank Warton – also one of the pilots ferrying Bernhardt’s carefully-chosen Markpress war correspondents to Biafra from Portugal.

Guns and Holy Butter

At least fifteen separate religious organizations with thousands of staff members were handling much of the ground logistics of the Biafran war. At the top of the organizing hierarchy was the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and CARITAS Internationalis, which created a cross-denominational, transatlantic humanitarian intervention volunteer group comprised of Catholic and Protestant churches called Joint Church Aid (JCA) on direct instructions from Pope Paul VI.

Beneath these two main coordinating bodies, other church groups from Germany, North America and Scandinavian countries ran their own relief and weapons smuggling operations. CARITAS and the UK’s Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (Oxfam) organized an aggressive media campaign across Britain, which brought in considerable resources. A contingent of clergymen and lay people working with the religious groups acted as spokesmen for the war, spreading unverifiable figures about the death and suffering caused by the blockade to the press flown in by Markpress.

Church officials in Western countries also did their part. The World Council of Churches (WCC), active on the ground in Biafra, was also very involved in the dissemination of war propaganda through their global reach. In England, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal Heenan of Sweden greatly expended the pool of UK donors by together directing the priests of the Westminster Archdiocese to appeal to their congregations.

By January 1969, the scale of the operation had grown to massive proportions. Once Markpress’ starvation angle began propagating in the collective consciousness through the Western media, resources began pouring in. The JCA leased a Hercules C-130 with a carrying capacity of 20 tons for a million dollars, with the ability to air-drop supplies without landing on dangerous airstrips. Catholic church organizations coordinated through CARITAS set up nearly 1,500 feeding centers servicing over 1.2 million people. The WCC, which organized many of the Protestant church groups, fed 1.5 million through its feeding centers.

Curiously, the Catholic distribution centers were based on the location of their dioceses, while the WCC’s used the provinces delineated in Ojukwu’s 1966 decree to organize its own. This odd division of labor has contributed to some of the most sinister allegations of what was actually happening on the ground in Biafra, with petty rivalries and animosities between the priests of the different denominations, including accusations of selective access to food and medicine that exacerbated malnutrition in certain cases, while reserving provisions for others, including the missionaries’ own children.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

An inescapable observation many people in Nigeria were surely aware of was the fact that virtually all of the relief organizations were based out of the same Western states either directly or tacitly supporting the Federal Government of Nigeria and making the blockade that was the cause of such misery possible. Bernhardt’s marketing campaign had managed to stop arms shipments to FMG from many countries, except from the ones already supplying them.

Conventional interpretations of the war in Biafra must be open to question in light of the tectonic shifts occurring simultaneously as the Anglo-American hegemonic project was floundering. Ojukwu’s breakaway movement in Eastern Nigeria demands reexamination in light of the crisis at the heart of neoliberalism in the latter half of the 1960s, with an understanding the critical role played by development finance in the imposition of a liberal trade order by London and Washington, putting aside more simplistic views of what was a much more complicated reality.

Reigniting the development finance sector, backbone of the so-called dollar standard, was a mission-critical endeavor for the Anglo-American project, as events in the immediate post-war period had begun to peel back the layers of the fraudulent nature of the international monetary system imposed at Bretton Woods. Europe, increasingly reliant on its own resources to rebuild, let the Marshall Plan wane, while Britain’s own development finance schemes in the former colonies to keep sterling’s value propped up and maintain its own balance of payments, was also staring down an abyss.

By the late 60s, the Vietnam war had fully exposed how the World Bank-IMF dollar-recycling game was being used to finance America’s war machine through deficit spending, which was in turn, facilitated through London’s merchant banking houses, which serviced the loans on behalf of the financial institutions, and of course, those of the UK’s CDC as well.

Evidence does suggest that Britain and the United States indeed wanted a war in Nigeria, but not for the reasons most readily assume. The West African nation had not even celebrated five years as an ‘independent’ country by the time its civil war broke out in 1967, and British influence on its internal affairs was still very strong. More significantly, the federal republic itself was a British-sponsored project, following continuations of Attlee’s decolonization policies and carried out in spite of the opinion of a majority of West Africans, who were skeptical about bringing the ethnically distinct regions together.

The impending debacle of the debt-finance regime did not come as a surprise to the Anglo-American neoliberal establishment, which had been watching the writing on the wall for some time. Finding new ways to keep the nations of the world shackled to the dollar-based debt system played an overarching role in most of the policies enacted in Britain and the United States during this tumultuous period in recent history.

A first salvo was launched as the critical 1960s were about to begin, with the United Nations’ General Assembly adopting resolution 1710 (XVI), which called for a “development decade” slated to run through 1970. Referred to as DD1, it is considered a cornerstone document of the “social development” paradigm that would become integral to development assistance programs over the coming years, but the underwhelming results by the middle of the decade drove the Anglo-American establishment to recalibrate their strategy.

One of the critical moments in this process took place at a dinner party in the country home of the UK’s former Minister of Education and intelligence officer, Sir Edward Boyle, just days after the July Counter Coup of 1966, when Yakubu Gowon came to power in Nigeria. The guest list included only World Bank Governor, George Woods, the head of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNSECO), Rene Maheu, and the highly-regarded development economist and mother of social impact investment, Barbara Ward.

Barbara Ward was raised Roman Catholic, and despite having a surname associated with one of Britain’s most notable Catholic families, Ward’s father was a Quaker with no relation to the Victorian blue bloods of the same name. Brought up to attend mass regularly by her mother, Barbara imbibed Walter Ward’s Quaker precepts as well, leaving a mark on her writings in The Economist and her many published works.

At just twenty-five, Ward had already published her first book, “The International Share-Out”, which tackled the burning questions of Britain’s colonial issues. While working on her PhD a year later at London University, she was invited to spend a week at the home of Arnold Toynbee, who was part of the faculty. Toynbee would take her under his wing and bring her into the Ministry of Information – an official UK propaganda outfit – until war broke out in Europe, at which point she transitioned to a full time position at The Economist on Toynbee’s recommendation.

Three years into her eleven-year stint at the British weekly, Toynbee’s Ministry of Information came calling once again and borrowed Ward for a five-month assignment in Washington, D.C. ostensibly to encourage America to join the war prior to Pearl Harbor. Working out of the British Embassy in the U.S. capital, Ward cut her teeth in international politics by meeting and socializing with high level contacts, such as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Vice President Henry Wallace and many others.

Her most important encounter in Washington was with Monsignor Michael Ready, the General Secretary of the National Catholic Welfare Conference (NCWC), the secretariat of American bishops. Ready opened the doors of the American Catholic community for Ward, which she herself acknowledged was “an obvious necessity if a trip of this kind” was not to be in vain. An odd diary entry considering the stated purpose of her long visit to a majority Protestant country.

However, Ward’s career trajectory would shed light on the “obvious necessity” of establishing a network of Catholic clergy in the United States. For the time being, Barbara would become a household name upon her return to the UK, after regular appearances on the BBC program Brain Trust alongside her boss at The Economist, making her popular enough to be considered as a Labour party candidate for the House of Commons in 1945. Although she demurred, Ward nevertheless campaigned for Ernest Bevin, who would become Secretary of Foreign Affairs in the Attlee government and spearhead the decolonization policy, aided by her fellow Toynbee protégé Sir Harold Beeley.

She also supported other Labour candidates that election cycle and once took her friend Kathleen Kennedy’s little brother, John, to a Herbert Morrison rally. The 28-year old Navy Lieutenant was reportedly “fascinated by the political process”, according to Ward’s diary entry about her day with the future, star-crossed president of the United States. Twenty-six years later, Barbara would be advising JFK on development projects in Africa, where she would reside for several years with her husband, Sir Robert Jackson.

When they met in 1943, Jackson was the principal advisor to the UK’s War Cabinet minister in Cairo and led the day-to-day operations of the Middle East Supply Center (MESC), a joint British-American civilian advisory agency handling shipping and distribution bottlenecks between multiple jurisdictions. An experience he would go on to apply as the post-war director of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and later as a technical, logistical and pre-investment consultant for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The New York Times’ obituary for Jackson called him a “founding father” of development assistance programs.

In 1961, Ward – who now went by “Lady Jackson” –, was leveraging her considerable influence in Washington to recommend that U.S. President Kennedy move forward with a hydroelectric dam project in Ghana, which her husband had been consulting on since the early fifties when the newlyweds moved to what was then still a British colony called the Gold Coast. The Volta River Project was a massive infrastructure deal that included the hydroelectric dam that would generate the power for a bauxite smelting plant to export aluminum.

In the works for several years, the project was the centerpiece of Kwame Nkrumah’s political platform. Nkrumah, a frequent visitor to the Jacksons’ home, would become the first president of the ‘decolonized’ Republic of Ghana in 1960, riding on promises of economic independence and self-sufficiency that the dam would bring. Kennedy acquiesced to Ward’s counsel and subsidized the project, which was built and operated by American aluminum and steel magnate Henry J. Kaiser.

When the dam was completed, it created the biggest man-made lake in the world and a humanitarian catastrophe, forcing over 80,000 people living upstream in small farms on their ancestral home lands to flee. The disaster was, in turn, exploited through the ‘intervention’ of the World Food Programme, which came to ‘help’ by exchanging food for labor. Adding insult to injury, Keiser conditioned his participation on using bauxite imported from the U.S. instead of local supplies, dashing the promises of self-sufficiency Nkrumah had made and causing irreparable damage to his reputation. By the time the Ghanaian president was deposed in a coup five years after Ward’s call to the White House, the Jacksons were long gone. But, Barbara Ward’s shining moment was yet to come.

The Pearson Commission

Boyle’s decision to invite Ward to discuss the “declining efforts in development assistance” that were putting the goals of the UN’s DD1 in peril was critical to the outcome of the meeting. It was she who suggested to the World Bank Governor, that the institution should assemble a “panel of experts to provide a blueprint for the future of North‐South relations”, which would become known as the Pearson Commission.

Over a year later in October, 1967, Woods stood before a group of international bankers at the Swedish Bankers Association conference in Stockholm, Sweden to deliver the keynote address titled “Development – The Need for New Directions“. In his speech, Woods urged his audience to “disperse some of this gray fog of suspicion and discouragement” that surrounded development programs by “constant repetition of the actual facts”. After rifling off a few statistics to buttress his argument, Woods digressed and suggested that “facts” alone would not be enough:

“One must suspect that the impact of good news is relatively slight on our strange human psyche, and that disasters and failures alone stay vividly in our minds. Perhaps, as King Lear suggested, we need not only to know the facts but to “sweeten our imagination,” if we are to see the development effort in its proper perspective.”

Woods immediately goes on to cast aside “normal methods” as a viable strategy to resolve “the problems of development at this stage of the world’s economic history”, before moving on to the topic of population growth versus technological advancement at a time when “farming is still insufficiently modernized to provide increasing food for the whole population”. Woods invokes none other than the oil refinery in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, as an example of the “unlucky disproportions” population growth can cause in a time when “the spurt of population is taking place ahead of the means of feeding and absorbing it”.

A curious choice, to say the least, as the Nigerian Civil War was only entering its third month and had yet to capture the world’s headlines. In fact, Ojukwu’s ministers hadn’t even met with Mr. Bernhardt in Portugal to set the terms of the contract for the international war propaganda campaign. That meeting would take place the following month and begin the process of sweetening the imagination, as Woods’ Lear might say.

The panel of experts suggested by Ward at Boyle’s country home more than a year earlier would remain on the back burner until the spring of 1968, when Robert McNamara, the architect of the Vietnam war and longest serving US Secretary of Defense in history, became president of the World Bank. Once there, Barbara Ward herself would guide McNamara’s selection of the panel members, which included Deutsche Bank executives, the former Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Douglas Dillon, and economist Robert Marjolin, who had overseen the implementation of the Marshall Plan in Europe. Boyle, a member of Britain’s development think tank, Overseas Development Institute (ODI), was appointed UK representative.

Lester B. Pearson, just recently replaced by Pierre Trudeau as Prime Minister of Canada, was chosen to chair the commission which would bear his name. Brought in as an alternative to their first choice of Oliver Stanley, the UK’s Colonial Secretary during World War II and the main proponent of the welfare policy strand that informed the creation of the Colonial Development Corporation, Pearson nevertheless performed the task he was given with aplomb.

Intended to produce a report that would serve as a tool to loosen the purse strings of wealthy European countries and revitalize the slumbering aid and development business, the Pearson Commission was heavily criticized by outside observers, who saw through the smoke screen and tagged it as a charade and called it a “gimmick” to recruit donor countries, according to one Indian economist. Pearson himself admitted as much, addressing complaints about the panel’s composition at its very first meeting by candidly stating that the appointments were a “[deliberate and] conscious choice made to preserve the credibility [of the Commission] in donor countries [even] at the cost of some resentment.”

The Pearson Commission’s report was published in 1969 and received with borderline contempt by economists generally, but hailed as “one of the most important documents of the twentieth century” by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, who clearly understood that the report had little to do with development per se, and was rather an instrument for the restructuring of the Anglo-American debt-finance system. In practical terms, the report was meant to dovetail with and provide international cover for development policies being fashioned in Washington simultaneously and which would be put forth by Nixon’s own Presidential Task Force on International Development headed by Bank of America CEO, Rudolph Peterson.

Throughout the course of the Pearson Commission’s work, the Canadian statesman was kept abreast of policy tendencies by State Department officials, USAID staff, and members of Nixon’s cabinet. It was understood that the content of the Commission’s final report would promote the main theme of Peterson’s future report, namely that all aid and development would henceforth be channeled through the World Bank.

McNamara wasted no time and implemented almost every single one of the Pearson Commission report’s 33 recommendations, exponentially multiplying the disbursement of International Development Association (IDA) credits and doubling the institution’s loans and borrowings in the first five years of his tenure at the Bank. Development finance was back in business, and in the UK the CDC adjusted its focus accordingly, where the underpinnings of what we now call social impact investment began to take shape.

Conspirators in the Vatican

When McNamara became the World Bank’s top executive, there were few people on earth better prepared to understand what neo-colonial resource wars looked like and the toll they can take on the warmongering nation’s Treasury. But his close advisor at the Bank, Barbara Ward, had tapped into greater forces of geopolitical manipulation and control. With nearly three decades of foreign intelligence work under her belt, the grand Dame of development finance had bent the ear of American presidents and presidential candidates since the 1940s. She’d help write speeches for Adlai Stevenson, become an advisor to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson; she lectured at Harvard on a four-year grant from the Carnegie Corporation and wrote several books on the subject of wealth redistribution, all in between traveling across Africa and Asia with her husband promoting Western-backed development projects.

However, her most important assignment would center on bringing the Vatican and its vast reach among the poor into the fold of Anglo-American global finance schemes. Ward’s Catholic upbringing and years of building her network of Catholic clerics and institutions would begin to pay off two years after the Second Vatican Council (a.k.a Vatican II) was inaugurated in Rome in 1962 by Pope John XXIII, who would die of stomach cancer only eight months later.

Labeled “the Pink Pope” due to his permissive attitude towards the Italian Communist Party, the CIA monitored the holy father’s activities as much as it could, but was precluded from direct surveillance by Pope John’s penchant to circumvent regular channels of communication, which as the pope well knew, were already crawling with CIA assets and operatives. As convenient as his death was, the spy agency’s involvement has never been convincingly established. Less disputed is the CIA’s role in the subsequent rigging of the Papal Election which placed Gladio collaborator and long-time American intelligence asset, Giovanni B. Montini, on the papal throne.

In the fall of 1964, not far from St. Peter’s Basilica where Vatican II was ongoing, Barbara Ward and Montini’s friend James J. Norris, who was the former wartime director of the NCWC’s European relief effort and then assistant executive director of its post-war incarnation, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), met in Piazza Navona at the behest of English Father Arthur McCormack, the UN’s consultant on population, to draft a pro-memoria (a formal diplomatic note) to present to the Vatican’s assistant Secretary of State, Archbishop Angelo Dell’Acqua to request a “poverty day” at the Council.

Joined by Msgr. Luigi Ligutti, of the National Catholic Rural Life Conference (NCRLC), Msgr. Joseph Gremillion from Louisiana, a Ligutti protégé who was then director of socio-economic development for Norris at CRS and executive secretary of the Pastoral Aid Fund of Latin America, the group dubbed themselves the “cospiratori”, Italian for conspirators. Through Norris’ connections the request seeking action by the Church on “problems of poverty and under-development” was bumped up to a formal address at the Council where Montini, now Pope Paul VI, would listen to the proposal in person.

Ward was originally supposed to deliver the presentation and become the first lay person in history to address an ecumenical council, but her recent separation from Sir Robert Jackson posed a public image problem and the honor fell to Norris, who stood before the Council and in his best Latin called to “secure full Catholic participation in the world-wide attack on poverty”. Norris was summoned to the office the Cardinal Secretary of State, Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, to receive a more detailed written proposal.

Cicognani, who years earlier had served as the Holy See’s apostolic delegate to the United States, was the Vatican official who secretly met with William “Wild Bill” Donovan in Washington D.C. to establish the first covert lines of communication between the Roman Catholic Church and American intelligence agencies, that would evolve into operation Gladio, and in a few short years after Norris’ historic appeal in St. Peter, plant the seeds of a worldwide development finance regime under the aegis of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) standards and other Fourth Sector protocols.

Road to War

Three weeks before the Vatican II Council was adjourned in December, 1965, the commission in charge of formulating the conciliar document included the work of Norris’ subcommittee in Paragraph 90 of the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, calling for the creation of a poverty/social justice secretariat. The process to bring this new, independent body inside the Vatican into reality would then begin, with Norris remaining in Rome for the next several months, where he would be tasked with tamping down opposition to the cospiratori’s plans.

On July 8, 1966, Pope Paul VI announced the formation of a “provisional committee” to move the establishment of the secretariat forward. UN Secretary General U Thant, a personal friend of Ward’s, and World Council of Churches (WCC) General Secretary Eugene Carson Blake both appeared before the provisional committee on behalf of Norris. A month later, Ward was meeting with Woods and company in Boyle’s home in full expectation of the secretariat’s impending approval.

Finally, on January 6, 1967, the Pope officially established the Pontifical Commission for Studies on Justice and Peace also known as Justpax. There was no time to lose and Ward, the only woman appointed to the commission, got to work only three months later instituting programs on two timescales, according to an interview with The Catholic Transcript. The short term plan consisted of increasing the “flow of capital resources from developed to developing lands”, while a longer term goal would seek to modify “the patterns of world trade”.

The creation of Justpax occurred just as Ojukwu and Gowon had concluded their seemingly successful meeting in Aburi, Ghana. Peace appeared to be on the horizon, but the illusion was soon broken a few days later by the publication of Tenneco’s fake articles warning about the dangers of the Libyan-style tax laws, sowing doubts among Gowon’s inner circle regarding the wisdom of Aburi. British High Commissioner Hunt sided with the skeptics, while U.S. officials reassured Gowon that they wouldn’t support Ojukwu.

On March 13, Ojukwu held an international press conference announcing that the Eastern region was moving towards “decentralization” and accused Gowon of reneging on the Aburi Accord and multiple instances of sabotage and incitement in a lengthy statement, where he denies rumors he had already decided to secede before Aburi; assertions that are contradicted by interviews appended to the same document where he tells Western media that he has been in position to “set up an alternative government” since July of 1966, but has restrained himself.

Even at this point, with Ojukwu threatening to implement the terms of the Aburi Accord unilaterally in the Eastern regions, Gowon continues to show patience and attempts to appease the Governor of the Eastern Region with Decree No. 8, which granted the territory considerable autonomy. Unfazed, Ojukwu passed his June Edict demanding all royalties from oil concessions in the Eastern territory be paid to the Biafran government. What should have been the last straw and clear casus belli for the FMG, which drew over 70% of oil revenues from the Eastern regions, failed to move Gowon.

The fact of the matter was that all the power rested with the oil companies themselves, particularly Shell, which was by far the largest oil concession holder in Eastern Nigeria and accounted for a 35% share of total royalty obligations. Had Shell simply continued to pay its royalties to the FMG, Gowon would have more than likely kept his troops stationed in the barracks and Ojukwu’s experiment would have failed.

Instead, Shell’s board of directors held a meeting in London where they reportedly decided to pay Ojukwu a token royalty payment of $250,000. The story was carried by the London Times on July 3, 1967. Gowon was infuriated, considering it an affront to his government and de facto recognition of the breakaway state. The war began three days later.

Pop Up Decolonization Shop

Biafra existed only as long as the humanitarian aid mission required it to exist. For two and a half years, the world witnessed an unprecedented media event, a reality-TV war, in which the heroes were the protagonists, while the misery and death a mere backdrop for the action with the script flown in daily from Geneva.

In early January 1970, Ojukwu handed power to his Chief of Staff Philip Effiong and fled to the Ivory Coast, where he was granted political asylum by Félix Houphouët-Boigny. Effiong was president of Biafra for five days, surrendering to Gowon’s forces on January 12. Eleven years later, Ojukwu returned to Nigeria and even ran for office (unsuccessfully) twice. He died in 2011 at the relatively ripe old age of 78.

For the citizens of the short-lived state of Biafra, many emigrated after the war and formed sizable diasporas all over the world. Those who stayed found that life returned to much the same way it had been before the war, with the most noticeable change being the steady environmental deterioration caused by the oil extraction process, which remains the largest industry in the area. The vaunted ‘development’ has yet to reach it.

Conversely, the Biafran conflict gave birth to the Non-Governmental Organization or NGO, which has since played an integral part in projections of soft power and the development finance game. Groups like Doctors Without Borders/Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF), Concern Worldwide and Church Relief and Development Association (CRDA) among others trace their origins to the Biafran war, which helped to rebrand the face of capitalism.

Barbara Ward continued her work in the Vatican. Pope Paul’s official letter to every Catholic bishop around the world, known as an Encyclical, titled “On the Development of Peoples [Populorum Progressio]”, which was published just before the conflict erupted with commentary written by Ward, was the basis for the 1971 Synod of Catholic Bishops, which sought to equate development finance with a spiritual mission and where Ward performed an official advisory role. That same year, she would be brought in as the public-facing co-founder of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), which established the underpinnings of “sustainable development” under the auspices of the think tank’s actual founders, Robert O. Anderson, chairman of the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO), and Joseph E. Slater, president of the Aspen Institute.

Once the Petrodollar system was put in place, the development finance regime was freed from the tethers of Britain’s sterling issues that gave birth to it in the first place, and became the backbone of a purely global agenda through the UN, IMF and the World Bank, which remained under the “forceful [and] active” leadership of McNamara until 1981 – a period characterized by the aggressive development loan tactics described by John Perkins in Confessions of an Economic Hitman.

The Multilateral Colonialism Model

Critics of the CDC’s big rebrand as British International Investment accuse the organization of abandoning its ostensibly egalitarian roots, but this is just an erroneous appreciation of its real origin story in the post-war Attlee government. “Decolonization” was as much a gimmick as the Pearson Commission and as contrived as the state of Biafra, and has since morphed into a quasi-spiritual, pseudo-universal quest for puerile notions of social justice and fraudulent environmentalism through the Anglo-American hegemonic project’s partnership with the Vatican.

British International divides the Crown’s neo-colonial territories into four categories: Mature, Powerhouse, Stable and Fragile. These designations mirror traditional monikers like ‘third world’ or ‘developing nations’ applied in previous eras, and are intended to identify the types and level of investment the UK’s ‘impact investor’ will allocate to each region. For instance, the “mature” economies of India and South Africa – the only ones so defined –, will count with a “bespoke country perspective/plan” and onsite personnel, as well as access to the full range of investment channels. The chart excerpted from the report below details each category:

The geographical regions could easily be overlaid on an 19th century map of Britain’s colonial possessions and, similarly, its investment portfolio coincides with those historical ties. Nigeria continues to be a focus of attention and has received the bulk of British International’s investments since the rebrand got rolling. The West African nation’s banking and finance sector also has the largest presence of any African country on British International’s board of directors.

Indeed, along with the Irish Catholic missions that arrived after the British Empire made it one of her colonies came her merchant bankers, who laid the groundwork for the development finance model. In 1925, Barclays Bank Chairman Sir William Goodenough established the bank’s international business concern with the creation of the Barclays Bank DCO (Dominion, Colonial and Overseas), which led directly to the passage of the Colonial Development Act of 1929, precursor legislation to what would be the Colonial Development Corporation years later. The CDC’s first director was a Barclays executive, who ran the bank’s Overseas Development Corporation (BODC), founded one year before the CDC itself. These old banking networks remain in place today on British International Investment’s executive and investment boards, together with additions from Sir Ronald Cohen’s flagship social finance think tank, Global Steering Group for Impact Investment.

Other notable individuals include Liz Lloyd, former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Deputy Chief of Staff and senior adviser on Africa, Home Affairs and the Environment. Blair’s Institute for Global Change is a major supporter of impact investment schemes across India. Lloyd is among the most active executives, serving on multiple boards. She is joined by former Deutsche Bank executive Holger Rothenbusch, member of the executive and investment committees, while also sitting on the board of British International’s so-called “platform” companies, MedAccess and Gridworks.

Described as “majority-owned subsidiar[ies]”, their platform companies are private sector vehicles that drive “significant amounts of capital from other sources” to their main portfolio investments; essentially funnels for outfits like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Clinton Foundation, Gavi Alliance and other non-profits in the case of MedAccess, which interlocks with British International’s healthcare technology investments in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

A large proportion of British International’s recent investments have gone to private equity firms, further obfuscating the pathways its money takes and the kinds of enterprises it actually ends up funding. Unsurprisingly, many of these firms are owned by Western interests or directly tied to Anglo-American financial institutions. Examples include TLcom Capitaland Novastar Ventures. The former is run by Bain & Company’s former technology sector director and Silicon Valley veteran, while the latter has close links to large American biotech interests.

Conclusion – Moving Backwards on the Digital Plantation

One of British International’s rare direct investments in a local African startup demonstrates the fundamentally dependent nature of the development finance endeavor. Moove was founded by Nigerians Ladi Delano and Jide Odunsi, and is touted as a shining example of direct economic development. Moove is a souped-up vehicle loan financing company that targets “mobility entrepreneurs”, a.k.a Uber drivers, to help them lease or purchase a car for the dubious privilege of working for a rideshare company.

Using terminology introduced into the capitalist lexicon by Ward and her acolytes, Moove frames car debt as “democratizing access to vehicle ownership”, and other cringe-worthy phrases so popular these days in corporate settings. British International leads the way for the wholesale rebranding of predatory capitalism when it describes Africa and the other targets on its list as having “some of the world’s most favourable conditions” for the transformation of “economies and landscapes” through “innovations” and “green technology”.

Development finance is also undergoing a rebranding and reintroduced as impact finance, which is tied at the hip to blockchain technologies and other cybernetic systems built over the last half century on the backs of underpaid, forced and in some cases actual slave labor across the ‘developing’ world. The new digital systems will require no less amounts of coerced labor, and in a time when phrases like “renewable energy” are incessantly whispered in our ear to mesmerize us at the dawn of the impact finance regime, it is more urgent than ever to realize that we are the renewable source of energy it seeks to harvest.